By Augustine Wong

If architecture, as a verb, is the act of constructing man-made environments, to deconstruct is to undo the work of architecture. And yet, deconstructivism exists as a prominent architectural movement that has been supported by renowned ‘starchitects’: Daniel Libeskind, Frank Gehry and Bernard Tschumi, whose unorthodox forms and compositions dazzle visitors who look upon their works. But deconstructivism does not take after its literal breakdown suggesting a deconstructed visual design style. Rather, it takes after constructivism — an avant-garde movement that came to prominence in the 1920s.

Constructivists refused to follow mimetic, classical Western styles that promoted realism such as Impressionism or Expressionism. As a movement mainly led by artists from Russia such as Vladimir Tatlin and Alexandr Rodchenko, shaped by Cubist influences, not only did they pioneer abstract art development, but applied the same approach to constructed objects, typography, textiles, furniture and theatrical design. Graphic design, seen in Figure 1 for example, can be read as works of art thanks to their contributions. Constructed objects, meanwhile, form the basis of deconstructivism. Like their art, their architectural proposals broke classical rules of composition and experimented with new, curvilinear forms rather than continue with traditional geometric forms in Figure 2.

Tatlin, Constructivism’s founder, used the movement as a way to contribute to a utopian vision of life following the Russian Revolution. Its form consisted of a glass cylinder, cone and cube, and employed iron and glass in a symbolic representation of a new, Russian machine age. As Arnason and Mansfield write, “it anticipated, and in scale transcended, all subsequent developments in constructed sculpture encompassing space, environment, and motion, and has come to embody the ideals of Constructivism.”

However, the movement was short-lived. Soviet state doctrine, which had previously vouched for Russian avant-garde artists as the pioneers of Modernism, changed its mind in 1921 and traded in the avant-garde for Socialist Realism, ironically returning to the Western mimetic form it had planned on avoiding at first. However, 1928 Le Corbusier had already pioneered the use of pilotis in Villa Savoye, the ground-breaking development that allowed for open plan layouts that would propel Modernism to dominate architecture until the 1980s.

It is no surprise, then, that deconstructivism developed in the late 1980s. Both deconstructivism and constructivism are similar in terms of how they broke the rules of pre-existing architectural styles. In a way, constructivism reads as the rejection of neoclassical architecture, while deconstructivism can be read as an extension of postmodernist principles.

Postmodern architecture had already been experimenting with circular forms seen in Figure 3, but came nowhere near the complex parametric manipulation of building surfaces that deconstructivism conceives, ostensibly due to a lack of computing power until the 1980s, when home computing became affordable. Nonetheless, architects had been developing deconstructivism without heavy computing power as will be examined further on.

Classical postmodernism leading up until the 1980s can be characterised to have a playful appearance with the tendency to appropriate culture and historical typology to pay homage to the contextual background behind the building. Venturi and his wife Denise Scott Brown, for instance, are one of them.

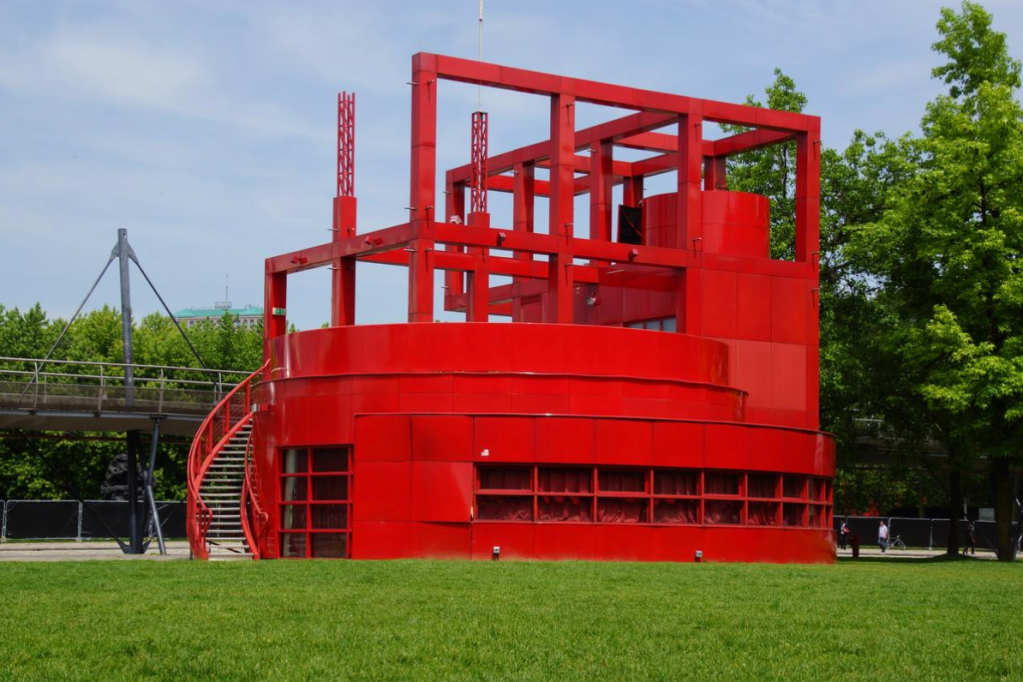

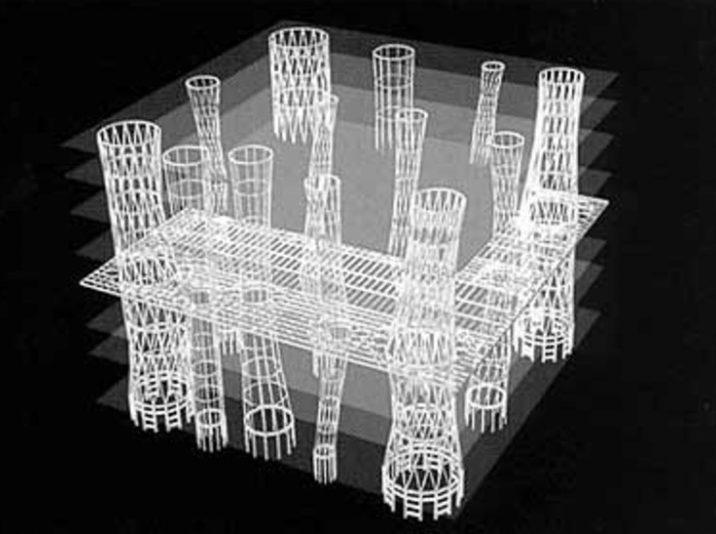

How did deconstructivism emerge from postmodernism? Architects identified as deconstructivists often deny the classification, such as Rem Koolhaas and Zaha Hadid, but arguably the movement began with Bernard Tschumi’s 1982 award-winning design, Parc de la Villette seen in Figure 4. If postmodernism was all about context, the deconstructivists destroyed that idea (or as Rem Koolhaas once said, [sic]. “Fuck the context.”) Tschumi turned the idea of park — then associated with ‘nature’ — to a programme based on ‘culture’. It was filled with irrationalities that defied Modernist principles, and represented the product of a highly conceptual approach to people’s sense of different scales in and out of Tschumi’s structure.

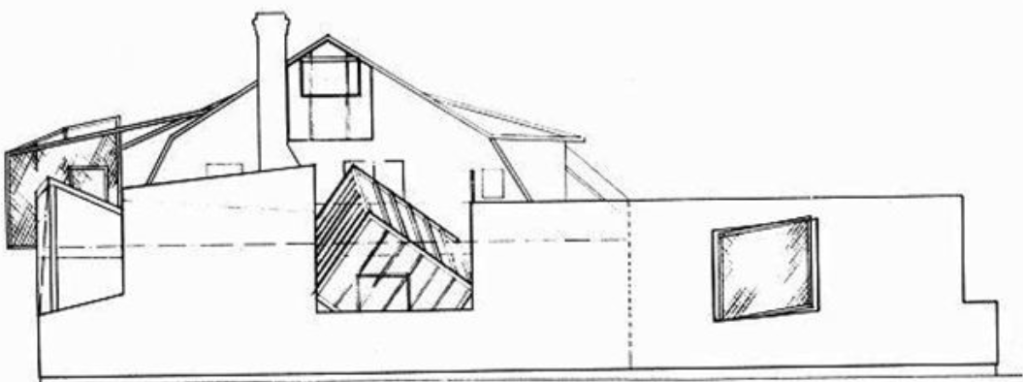

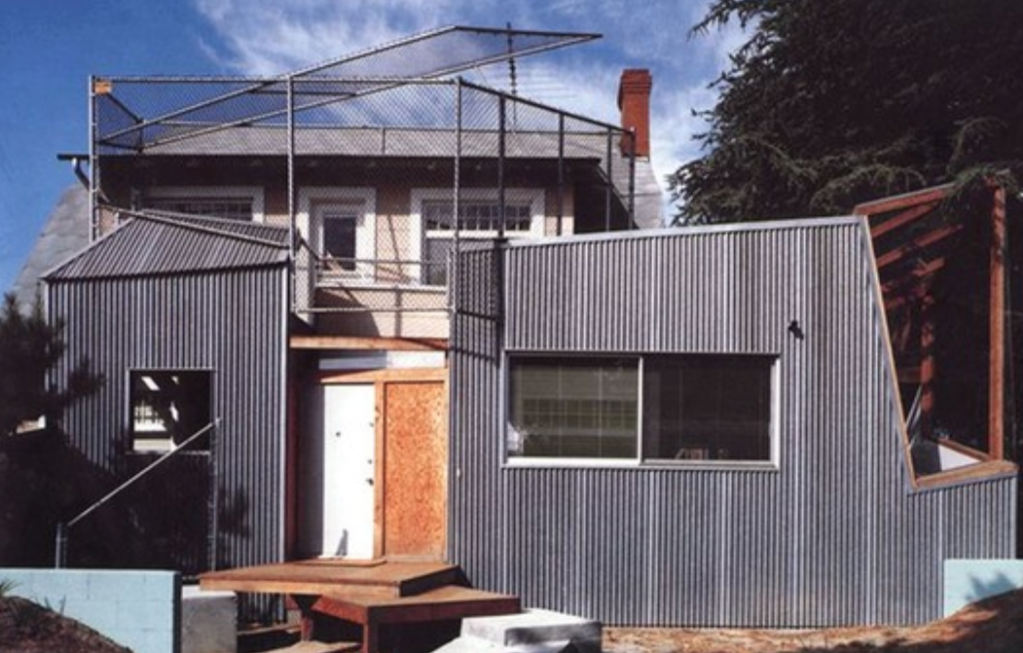

Tschumi was not the only one responsible for developing the movement. Frank Gehry had caused a stir four years earlier when he renovated a Dutch colonial house into a symbol of deconstructivism. Once again, irrationality prevailed. Gehry rearranged elements of a typical Santa Monica home in a radically irregular geometric fashion, like placing chain link fences around 2nd floor windows and translating axes of orientation. While the original house is completely intact, Gehry had created the impression of a house in mid-explosion.

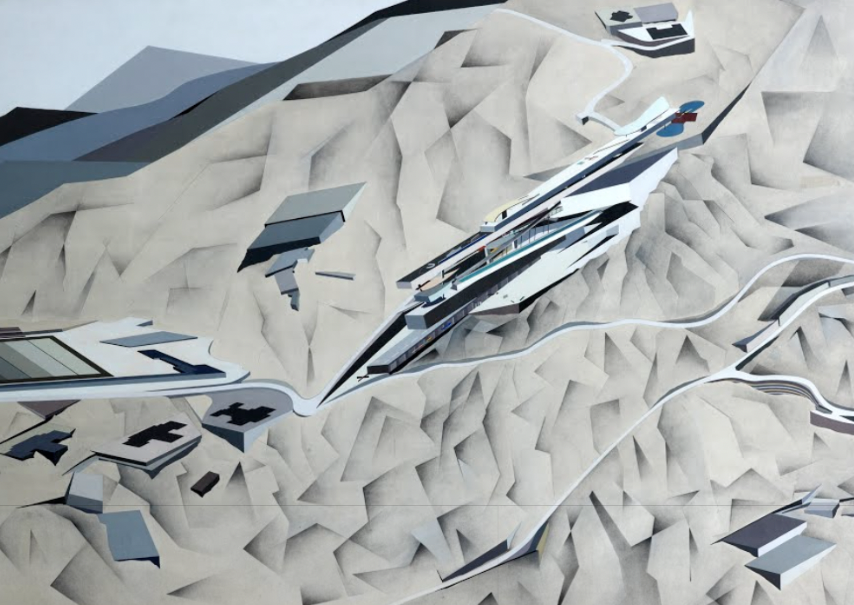

More architects soon emerged. The late Zaha Hadid, responsible for the Jockey Club Innovation Tower at PolyU (completed 2014), also had early beginnings in geometric deconstructivism. In 1982, the award for a competition for a new private club was awarded to Hadid’s entry, The Peak Leisure Club. The proposal consisted of a multi-layered, horizontal skyscraper that acknowledged Hong Kong’s vertical skyscraper culture — and poignantly proposed to build horizontally instead. Her complex, shattered forms were later associated with deconstructivism. All the works for the entry were done by hand, reading as a work of Suprematist art.

These examples are only a fraction of the works that flourished in the 1980s. By 1988, a symbolic turning point emerged. The exhibition Deconstructivist Architecture, curated by Phiip Johnson and Mark Wigley, was held at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, which showed a compilation of works and models by spearheaders of the movement: Coop Himmelblau, Peter Eisenman, Frank Gehry, Zaha Hadid, Rem Koolhaas, Daniel Libeskind and Bernard Tschumi. Unlike previous architectural movements like Modernism, led by formal groups like CIAM and Team 10, Philip Johnson curated these architects by their similarities in work, not by architecture formed on a specific set of rational principles.

What similarities did Johnson and Wigley see in their works? Deconstructivism is known for its tendency to fragment structures, manipulate structural surfaces (known as skin), and redefine shapes and forms which results in a style that appears visually deconstructive to the viewer. The deconstructivist desire to overturn Modernist scientific rationality in exchange for irregular geometry and dynamic forms results in an impression of controlled chaos. A visitor to the Bilbao Guggenheim Museum, for example, may be overwhelmed by the large, curvilinear volumes under dazzling Spanish sunlight. However, deconstructivist works have roots in mathematical relationships in contrast to the chaotic appearance that the sum of its parts produce. On top of that, deconstructivists often reject the label, generating further uncertainty around the principles of deconstructivism, but the 1988 exhibition showed that these pieces were chosen for their similarities in respect to:

- Fragmenting volumes

- Rejecting symmetry and regular geometry

- Lack of harmony and continuity in terms of context – works like the rooftop remodelling by Coop Himmelblau in Vienna (completed 1989) does not harmonise with the surrounding classical environment, for example.

- Lack of right angles and irregular lines

- Use of disproportionate and distorted volumes

- Focus on conceptual development and disrupting how architecture and space is perceived.

Deconstructivism continued well into the 1990s and into the present. With the advent of computing power, deconstructivist architecture could afford to explore more curvilinear forms. Architects manipulated curvilinear forms more often, such as Frank Gehry, MAD and Zaha Hadid to explore fluidity, for example, as part of their conceptual approach to architecture in Figure 8.

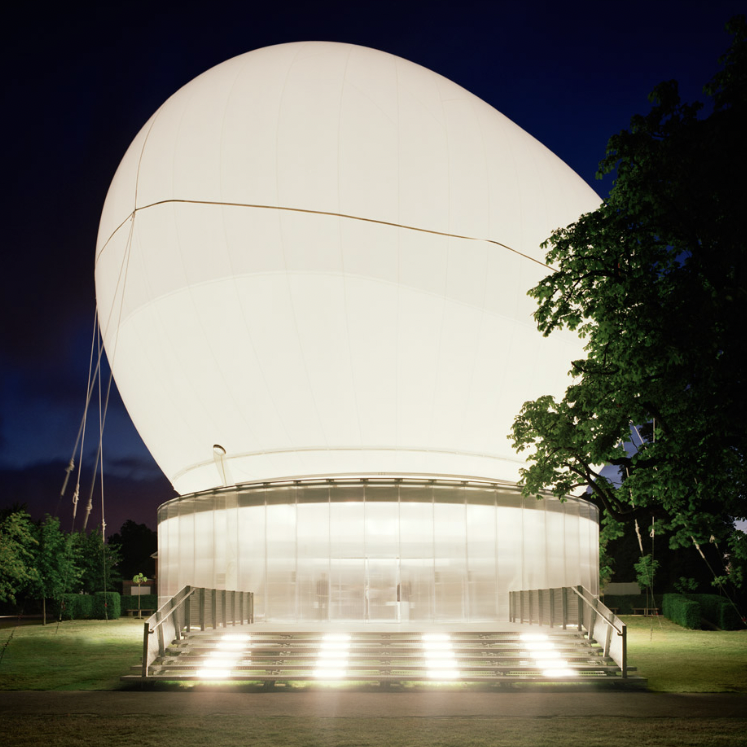

On the other hand, deconstructivism has evolved to have broader architectural definitions when considering a lack of rigidly defined principles that allowed it to form organically in the first place. As a highly conceptual movement, the movement does not necessarily manifest obviously through formal qualities. Toyo Ito and Rem Koolhaas, for example, prioritise programme in their design. For example, Toyo Ito’s Mediatheque in Sendai (completed 2003) attempts to dissolve the distinction between structure and infill by emphasising open floor plans that created a continuous landscape. Rem Koolhaas’ Serpentine Gallery Pavilion, meanwhile, was designed as a public forum for 24-hour interview marathons, but with the addition of an ovoid-inflatable canopy that looms over the pavilion. In a way, this canopy challenges Modernist architecture’s need for rigid rational forms further, as it inflates and deflates based on weather conditions, and embodies the deconstructivist vision of ‘controlled chaos’. Both considered plan layout strongly, which demonstrates another way that deconstructivism can be conceptual without being visually evident.

In summary, deconstructivism is a complicated movement that is still evolving rapidly thanks to its widespread dissemination and adoption by prominent architects. While it took inspiration from constructivism from the 1920s, it can be seen as an extension of Postmodernism. Both were counter-responses to Modernism, but Postmodernism rejected Modernism’s ignorance towards historical and cultural context, while deconstructivism chose to reject Modernism’s pursuit of scientific rationality and geometric form. First fighting back in 1978 with Frank Gehry’s use of radically irregular geometry in the Gehry Residence and formally recognized as some sort of collective in 1988, it has gone above and beyond to produce most of the eye-catching architectural products of our time, with Zaha Hadid as a leading example whose international works and groundbreaking forms made her a household name. However, not all deconstructivist work aims to use formal features to define itself, though it is generally characterised as so. Rem Koolhaas and Toyo Ito’s focus on plan and programme demonstrate an abstract, more purist approach to deconstructivism that suggests that pure conceptualism is the propelling force behind their works instead. If this is the case, where does conceptualism begin and deconstructivism end? It is too early to tell. After all, deconstructivism has no proper definition in contrast to older movements. One might consider it as an architectural style or a fancy label, rather than a movement with clear, intellectual goals. Perhaps a critic will come up with something more meaningful than this article.